| ||||

|

| |||

| Metis'e Dair |

|

|||||

|

Metis Yayınları 1982 yılında kuruldu. Üniversite yıllarında dönemin sosyal muhalefet hareketlerinin içinde yer almış Sol görüşlü 5-6 üniversiteli genç, kendi kişilikleri ile eğitimini aldıkları meslekleri arasında ilişki kuramayıp kültürel ve siyasi bir odak olarak Metis yayınevini kurdular. Araştırmayı, doğru bildiklerini sorgulamayı, tartışmayı, öğrenmeyi sürdürmeyi amaçlamışlardı. Bu ilk ekipte yer alanların bir kısmı daha sonra mesleklerine ve diğer ilgilerine yöneldiler. 1987 yılına kadar sadece edebiyat dışı kitaplarla ilgilenen yayınevi, bu tarihten sonra Türkçe ve çeviri edebiyat ürünleri de yayınlamaya başladı. Zaman içinde çeşitlenen kitaplar farklı dizilerde kümelendi. Aşağıda 1982-2004 yılları içinde yayınevinin kitap, yayıncılık, okuma, eleştiri düşünce ve ifade özgürlüğü temaları etrafında topluma kendini ifade aracı olarak gördüğü çeşitli kampanyaları hakkında bilgiler var. Metis’i en iyi bu kampanyaların anlattığını düşünüyoruz. |

|

1982

Yaşasın Kitap Yayınevinin ilk faaliyet yılları 12 Eylül askeri darbesinin de ilk yıllarıydı. Darbe ve onu takip eden rejim tam anlamıyla düşünce ve kültür düşmanı bir iklim yaratmıştı. Rejim eline geçirdiği muhaliflerini "herkese ibret olsun" diye kendi televizyonunda gösteriyordu. Gösterirken de silahların yanında kitaplar da sergileniyordu. Kitap bir suç aleti ilan edilmişti. Bu koşullarda asıl işimizin kitapları suç sayan zihniyetle mücadele etmek, kitapları ve kitap okumayı suç olmaktan çıkarmak olduğunu düşündük. "Yaşasın Devrim" diye sokaklara dökülmüş bir kuşaktan geliyorduk ve birden içimizden çıkıveren "Yaşasın Kitap" lafı, ruh halimizi çok iyi anlatıyordu: Hem ezikliğimizi silip başımızı dik tutabilmemizi, o kasvetli, bunaltıcı havayı dağıtabilmemizi sağlıyordu, hem bizi kendi geçmişimize bağlıyordu, hem de kitaplardan medet umduğumuzu gösteriyordu. Gerçekten de kelimenin tam anlamıyla kitaplardan medet umuyorduk. Öğrenmek, doğru bildiğimiz şeyleri sorgulamak, kendi hatalarımızla yüzleşebilmek, ve bu niyetle kitap okumak için bir iştah çıkmıştı ortaya ve "Yaşasın Kitap" bunu çok iyi ifade ediyordu. Daha sonra da uzun yıllar bu sloganı kullandık. Başka yayıncılar da kullandı ve giderek daha geniş bir çevreye maloldu. |

|

1985-86

Kitabı Geri Getirelim Burada anlattıklarımızın, okurlarımız tarafından "küçük bir dayanışmanın tarihi" olarak okunmasını isteriz. Bu önemli, çünkü anlattığımız olgular, insanlar ve kurumlar arasındaki iletişimi ve işbirliğini (çoğu zaman küçük olan) farklılıkları kullanarak sekteye uğratan, tahrip eden, "üzüm yemekten ziyade bağcı dövmeyi" telkin eden egemen ideolojiyi boşa çıkaran sivil girişim örnekleridir. 1980’den önce yayıncılar, o günlerin Türkiyesi’nin olanakları içinde de olsa, beklentisi belli bir okura, kurulu ve işleyen iletim mekanizmaları aracılığıyla seslenme olanağına sahiptiler. Oysa 12 Eylül darbesi, toplumun başka alanlarında olduğu gibi, kitapçılıkta da büyük bir tahribat yapmıştı. 1980 sonrasında yayıncılığa başlayanların karşısında çok hazin bir tablo vardı. Ne hazır bir okurdan söz edilebilirdi, ne de işleyen bir dağıtımcı/kitapçı kanalından. Okur ürkütülmüş, sindirilmiş ya da sadece ilgisini yitirerek bezmiş durumdaydı. Televizyon ve basında kitabın tekrar tekrar suç unsuru olarak vurgulanması, hakim ideolojinin artık "kendi başının çaresine bakma zamanı olduğunu" vazedip durması, genel bir durgunluğa yol açmıştı. Aynı şekilde sindirilmiş olan ve kendilerini tehdit altında hisseden kitapçılar da kırtasiye/oyuncakçı'ya dönüşüyorlardı. Bu durumda yayıncıları bekleyen, bir meslek dalı olarak varlıklarını koruma/sürdürme olanağını yaratmak, okur/dağıtımcı/kitapçı üçgeninin her birine ayrı ayrı seslenerek sektörün canlanmasını sağlamaya çalışmaktı. İşte "Bab-ı Âli'de hiç olmayacağı iddia edilen" yayınevleri dayanışması bu ortamda, ağırlıklı olarak yayıncılığa 1980 sonrasında başlamış, işlerini salt ticaretten çok bir iletişim aracı, kendini ifade biçimi olarak gören yayıncılar arasında başladı. İlk girişim 1985 yılında on altı yayınevinin (Akıntıya Karşı, 4 Eylül, Hil, İmge, İnsan, Kadın Çevresi, Kaynak, Metis, Nisan, Öncü, Sokak, Sorun, Sungur, Toros, Yazın, Yol) başlattığı "Kitabı Geri Getirelim" kampanyası oldu. Kampanyanın bir ucu, basının desteklemek amacıyla ücretsiz bastığı ve "Zamanıdır eski sorulara yeni yanıtlar aramanın", "Dünya yasaklarla dolu. Bir de biz kendimize kitabı yasaklamayalım", "Gün gelecek kimse 'utanmayacak' okuduğu kitaptan... O günlere hazırlanalım. Bir ütopyayı gerçek kılalım" gibi mesajlar içeren ortak imzalı ilanlardı. İlanların metin yazarlığı, şimdi polisiye yazarı olarak tanıdığınız Celil Oker tarafından yapılmıştı. Yayıncılar ayrıca ortak bir katalog basarak bunu ülkenin dört bir yanındaki 200 kadar kitapçıya yolladılar ve onlarla bir diyalog başlatmaya, onları desteklemeye hazır olduklarını bildirdiler. Oğlak Dönencesi’nin Yasaklanmasına Karşı İkinci kez yayıncıları harekete geçiren, Can Yayınları'nın bastığı, Fatma Aylin Sağtür'ün çevirdiği Henry Miller'ın Oğlak Dönencesi adlı kitabının yasaklanması oldu. Birinci basımı 1985 yılında yapılan kitap hakkında 19.2.1986 tarihinde TCK 426'ya dayanarak dava açılmış, 22.3.1988 tarihinde 1986/114 Esas, 1988/123 Karar sayısıyla sanıklara 426'dan ceza, kitaba da 427'den zoralım ve imha kararı çıkmıştı. Yayıncılarınen çok dikkatini çeken, kitabın yasaklanma gerekçesi oldu. Kitap, TCK'nın 426. maddesine göre müstehcen nitelikte bulunmuştu. Oysa bu kanunun altıncı maddesine göre, "Fikri, içtimai ve bedii kıymeti haiz olan eserler bu kanunun şümulünden hariç" tutuluyordu. Mahkemenin, Başbakanlık Küçükleri Muzır Neşriyattan Koruma Kurulu Başkanlığı Bilirkişi Raporu'nun "Objektif ölçülere örf ve adetlere bağlılığı, bilgi ve kültürü orta seviyedeki kişilere göre yapılan değerlendirmede kitabın, halkın ar ve haya duygularını inciten, cinsi arzuları tahrik ve istismar eder nitelikte genel ahlaka aykırı bulunduğu, sanat eseri mahiyeti taşımadığı (a.b.ç)" yolundaki yorumuna dayanarak verdiği karar, Henry Miller'ın kitabının "sanat eseri olmadığı"nı da saptamış oluyordu. Henry Miller'ın dünyaca tanınmış, saygın bir yazar olması bir yana, bir kitabın sanat eseri olup olmadığını saptama hakkının mahkemede değil, okurda olduğunu savunan yayıncılar, bu kararın bir de "kitap imhası" ile sonuçlanması üzerine sessiz kalamayacaklarına karar verdiler. Toplam 99 yayıncıyla yapılan görüşmelerden sonra, yayıncılardan 60'ı genelde şu iki gerekçeyle bu konuda ses çıkarmayı reddettiler: 1) Mahkemelere düşme korkusu; 2) Şimdiye kadar Türkiye'de onca kitabın imhasına sessiz kalınmışken, şimdi bu kitaba ses çıkarmanın bir gerekçesini göremeyişleri. İşin ilginci, yayıncıları temsil ettiği iddiasında olan, üstelik toplatılan kitabın yayıncısının da üyesi bulunduğu Yayıncılar Birliği'nin (Yay-Bir) bu konunun üstüne gitmeyi ve kitabın yeniden basımında yer almayı reddetmesi oldu. Bu imhaya itirazı olan 39 yayıncıysa, "Korku ancak yeni korkma olasılıkları doğurur," ve "Şimdiye kadar susmuş olma ayıbı hepimizin, ama bu şimdi bir kez daha susmanın gerekçesi olamaz" görüşüyle, kitaba sahip çıkma kararı aldılar. Kitabı tekrar basmaya, ama tekrar toplatılmasına engel olmak amacıyla, kanunun kendilerine tanıdığı bir haktan yararlanarak, Oğlak Dönencesi'nin Muzır Kurulu Raporu'nda ve Savcılık iddianamesinde yasaklama gerekçesi olarak belirtilen yerlerini çıkartıp, başına bu raporu ve savunmayla kararı eklemeyi kararlaştırdılar. Böylece kitabın bütünü, ekleriyle, "mahkeme serüveni"yle birlikte ve biraz "parçalanmış" halde, arkasında "Kitaptan Korkulmayan Bir Dünya İçin" ibaresiyle 39 yayınevi tarafından (Ada, Adam, Afa, Amaç, Ayrıntı, BDS, BFS, Birey ve Toplum, Boyut, Çaba, Çınar, De, Dost, El, Eleştiri, Gür, Habora, Hil, Hüryüz, İletişim, İnter, Kalem, Kaynak, Kavram, Kıyı, Kuzey, Metis, Nisan, Oda, Öykü, Pan, Savaş, Söylem, Teori, Toros, V, Yaprak, Yazın, Yön), 10.5.1988 tarihinde yeniden basıldı ve aynı gün, 1. Sulh Ceza Hakimliği'nin 1988/71 no.lu kararıyla toplatıldı. Yayıncıların toplatma kararına itirazları da 2. Asliye'nin 1988/24 D. İş kararıyla reddedildi. İstanbul Cumhuriyet Savcısı Aytaç Tolay, 1988/31 Hazırlık, 1989/133 Esas, 1989/57 İddia numarasıyla İstanbul 2. Asliye Ceza Mahkemesi'ne TCK 426/1 ve 427/son'dan dava açtı, ayrıca TCK 119'un da uygulanmasını istedi. Kısacası müstehcen nitelikli kitap yayınlama suçuyla açılan bu davada, yayıncıları 25 avukat gönüllü olarak savundular. Yerli ve yabancı basının ilgisini çeken davada sanıklar genel olarak kitap yasaklamalarına karşı olduklarını, bunu bir insanlık suçu saydıklarını, kitabı yeniden basarken bunu protesto etme gayesi taşıdıklarını belirttiler; ayrıca Henry Miller'ın kitabının bir edebiyat eseri olması nedeniyle, Muzır Kurulu'nun kapsamına zaten giremeyeceğini söylediler. Ayrıca, kitapta müstehcen bulunan bölümler sadece Muzır Kurulu Raporu'nda geçtiği için, aleyhte verilecek karar bu raporun müstehcen olduğunu belirtmiş olacaktı! 26.5.1989 tarihinde başlayan duruşmalar, henüz sanıklarının tümünün ifadesi alınmadan, 4. duruşmada beraatle sonuçlandı. 1989/155 Esas, 1989/230 Karar no.lu 26.9.1989 tarihli beraat kararında, "... yasalarımıza göre karara bağlanmış davalarda verilen karar örnekleri, bilirkişi raporları ve iddianame örneklerinin yayınlanmasında herhangi bir suçun oluşmaması karşısında müstehcenlik hususlarının çıkarılmak suretiyle bu belgelerin eklenmesi ile meydana getirilen kitapda sanıkların üzerlerine atılı bulunan ... suçun yasal unsurlarının oluşmadığı" söyleniyordu. Mücadelemiz tutmuştu, biz kazanmıştık... Kara Kitap İçinde varoldukları ve çalıştıkları ortamı "soluk alınabilir" bir ortam kılma yolunda üzerlerine düşen sorumluluğu yerine getirmeye hazır olan yayıncıların üçüncü ortak girişimi, 1 Ağustos Genelgesi'nin yol açtığı Eskişehir ve Aydın Cezaevleri açlık grevlerinin öyküsünü anlatan, Gaye Boralıoğlu ve Ayşegül Devecioğlu'nun hazırladıkları "Kara Kitap"ı basmak oldu. Bu kez 20 yayıncı (Afa, Alan-Belge, Amaç, Arkadaş, Ayrıntı, BDS, Boyut, Can, Çınar, Eleştiri, Gerçek, Habora, İletişim, İnter, Kavram, Metis, Nisan, Patika, Pencere, Sorun) demokrasi mücadelesinin bir parçası olduğunu düşündükleri bu açlık grevleri ile ilgili kitabı basma gerekçelerini "... Uzun bir soluğu gerektiren bu mücadeleye küçük bir katkısı olması amacıyla ve toplumumuzdaki hakim belleksizliğe bir uyarı olması umuduyla" diye açıklıyorlardı. Okuru canlandırmaktan kitapçıları desteklemeye, kitabı düşmanca saldırılardan korumaktan genel bir demokrasi mücadelesi vermeye kadar her alanda sorumluluk almak, ülkemizdeki yayıncıların varlıklarını koruyabilmesinin tek koşulu... Bu yüzden de bu tür dayanışmaların daha çok görüleceğini söylemek pek yanlış olmaz. |

|

|

1989

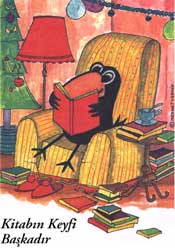

Kitabın Keyfi Başkadır Koltuğuna gömülmüş kitap okuyan karga resmini Mehmet Ulusel çizdi. "Kitabın Keyfi Başkadır" cümlesiyle, bir yandan okumanın seyretmekten, konuşmaktan, vb. insan etkinliklerinden farklı bir zevk kaynağı olduğunu, diğer yandan da bir görev, zorunluluk, ya da yük değil, bir haz kaynağı olduğunu vurgulamak istedik. Bugün de buna inanıyoruz. Kişisel haz ile ilişkisi olmayan, yani okuyan kişi için haz üretmeyen hiçbir gerçek okuma olamaz. Okunan şey bir çizgi roman da olsa, ders kitabından bir pasaj da olsa, gerçek bir okuma ancak okuyanın zevk alarak okuduğuyla buluşmasıyla mümkündür. Bunu şöyle de ifade debiliriz: Pek çok siyasinin, eğitimcinin ve aydının zannettiklerinin ve vazettiklerinin aksine "otomatik aydınlanma" yoktur. Otomatiğe takarak bilgilenmek ya da bilgilendirmek mümkün değildir. Bilgi bir sürahiden, boş olan başka bir sürahiye boşaltılan su gibi birşey değildir. Bilgi her zaman psikolojik ve etik süreçlerle birlikte yürüyen bir şeydir – hem bireysel anlamda hem toplumsal anlamda. Dahası kitaplar, balıkyağı ya da ilaç gibi vücuda yararlı olacak diye içilecek şeyler değildir. Kitaplarla ancak keyif alarak ilişki kurulabilir. Bu resim ve slogan çeşitli yıllarda kitap ayraçlarında ve takvimlerde kullanıldı. İlk kullanımlarında okuyan karganın yanındaki sehpada kahve –tabii tercihe göre çay da olabilir– fincanının yanında, içinde sigara tüten bir küllük de vardı. Günün birinde kütüphaneci bir okurumuz, yılbaşı akşamında bile kitap okuyan Metis kargasını çok sevdiğini, ama sigara içmesini, gençliğe yapılan kötü bir telkin saydığını söyleyerek eleştirdi. Biz de hak verdik – 1997’deki kullanımında kül tablasını kaldırdık. |

|

1991

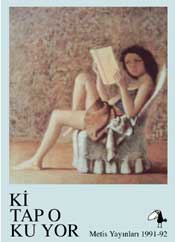

Ki-tap o-ku-yor (Katya kitap okuyor) Bu kampanya, Metis’in okumaya yaklaşımını ifade edebilmek için hazırlanmıştı. Posterde kullanılan resim Balthus’un ve "Katya Okuyor" adını taşıyor. Tasarım ise yayınevinin editörlerinden Semih Sökmen’e ait. Balthus’un bu güzel resmi okurlarımızdan büyük ilgi gördü. Posterin yazı kısmını keserek kullananlar olduğu gibi, birçok kişi de "Kitap Okuyor" cümlesini neden hecelettiğimizi merak etti ki, amaçlanan da zaten buydu. Kitap Okuyor— yani bunu yapmayı tercih etmiş. Kitap okumak, son derece kişisel, bireysel bir tercih meselesidir. İnsan kendi kendisiyle, yalnız kalabilmelidir ki okuyabilsin. Yani herşeyden önce, gündelik hayatının bir parçasında kişinin yalnız kalabilme cesaretini gösterebilmesi lazım ki okuyabilsin. Okumamaya gösterilen ilk gerekçelerden biri olan vakitsizlik bununla yakından ilişkili. Kanlı canlı hayata dönmek, insanların arasına katılmak, gevezelik etmek, konuşmak, izlemek, seyretmek varken niye yalnız kalalım ki? Ama öyle görünüyor ki, bunu tercih ve zevk edinen kitleler değilse de bireyler var. Bu yüzdendir ki Metis’te kitap yayınlarken hep şahsa, bireye seslenmeyi tercih ettik. Kitap Okuyor— o okuyor. Kitap okuyan hep üçüncü şahıstır. Okumayan bizler karşısında okuyan birey, tek başınadır, yalnızdır, bizden farklıdır, aykırıdır, ve ne tuhaf, kendi kendine de eğlenebilmekte, yaptığı bu tuhaf işten haz bile duymaktadır. Okuyan —dünyanın her yerinde öyledir ama Türkiye’de iyice öyledir— hep üçüncü şahıstır. Kitap Okuyor— ki – tap o – ku – yor. Okumayı öğrendiğiniz çocukluk günlerini hatırlayın. Harflere, işaretlere ve bunlarla anlam arasındaki ilişkilere şaştığınız zamanları hatırlayın. Yetişkinleştikçe ve daha fazla okudukça giderek okunanlar şaşırtıcılıklarını kaybederler. Yazı bir tür teknolojidir, okudukça bir teknik öğrenmiş oluruz – aynı kulağımızın müziğe alışması gibi, sonra müzikal türlere alışması gibi… Bu süreçte hem kazanırız hem kaybederiz. Çünkü yavaş yavaş okuduklarımızı sorgulamamaya başlarız. Yazı karşısında bir tür yorgunluk duymaya , otomatik okumaya başlarız. Ama yine de ara sıra geçmişte bir yerlerde kaybettiğimiz o çocuk gözlerimizi bize tekrar geri getiren metinlerle karşılaşacağızdır. İşte okumanın asıl keyfi, herhangi bir kitabın bizi böyle tekrar şaşırtabilme kabiliyetinde yatar. |

|

1992

Aa! Kitap Okuyor "Ki–tap o–ku–yor" kampanyamızın devamı niteliğindeki posteri Latif Demirci yaptı. Kitap okuyanın "özel bir tür olduğunu" vurgulamak için Latif’le birlikte kendi kendimize şu soruyu sorabiliriz: Bir Türk sabahtan akşama kadar ne yapar? (Tabii Türk’ün yerine gönül rahatlığıyla "Kürt" de diyebilirsiniz) Ödev yapar, kavga eder, Avrupa Birliğine girer, askere gider, okey oynar, makyaj yapar, dedikodu yapar, kabul günü yapar, kadınları rahatsız eder, oyuncaklarını kırar, top oynar, televizyon seyreder, çamaşır bulaşık yıkar, canını sıkar, içki içer, para kazanır, kazanmaya çalışır, ölmeyi bekler. Yanlış anlaşılmak istemeyiz. Okumak bir zorunluluk değildir. Okumayanları hor görüyor da değiliz. İnsan pekala okumadan da gül gibi yaşayıp gidebilir. Bizim söylemek istediğimiz bütün bunlardan çok sıkıldıysanız, kitapların önünüze başka bir dünya açabilecek olduğudur. |

|

1993

Elimizde Düşlerimizden Başka Ne Kaldı ki? Moralimizin hayli bozuk olduğu bir zaman olsa gerek. Fazla kırık, bezgin ve kaçak. Beklentilerimizin, umutlarımızın tam tersi yöndeki toplumsal gelişmeler karşısında şaşkınız. Tabii daha sonra bol bol şaşırmaya devam edeceğiz, ama belki de ilk kez böyle ağır duyuyoruz. Bu duygular içinde tavanarasındaki odasında okuyan ve okuduklarından çok etkilenen Don Kişot dikkatimizi çekiyor. Okumanın fantastik yanını, hayallerimizle ilişkisini vurgulamak istiyoruz. Kitapların düşlerimiz gibi dünyalar yaratabileceğini, o dünyaların tek sahibinin biz olduğunu, kitaplarla ferahlayabileceğimizi söylemek istiyoruz. O yılın kataloğunda Bilge Karasu, Murathan Mungan, Latife Tekin ve Juan Goytisolo’dan okuma üzerine pasajlar var. Şunları anlatıyorlar: Murathan Mungan Hiçbir işim olmasaydı, yazar da olmasaydım, tek işim kitap okumak olsaydı, hayatımı kitap okuyarak kazansaydım, bunun için maaş bağlasalardı bana ve elime çok iyi para geçseydi, yanı sıra hiçbir yükümlülüğüm olmasaydı, yalnızca canımın çektiği kitapları, merak ettiğim yazarları, ilgilendiğim konularda yazılanları okusaydım, günümün büyük bölümü yazmakla, ya da "yazar okuması" diye adlandırabileceğim, yazmakta olduğum şeyle ilgili kimi kaynak kitapları okumakla geçiyor; bu tür okumalar her zaman keyif verici olmadığı gibi, zevk almasam da sürdürmek zorunda kalıyorum; tabii bunlar da olmasa, paşa gönlümün istemediği hiçbir şeyi yapmak zorunda kalmasam, "Mesleğinizi seviyor musunuz?" diye soran gazetecileri, "Aa, tabii, çok çok seviyorum, dünyaya bin kere gelecek olsam gene aynı işi yapmak isterdim," diye yanıtlasam, beni her yıl düzenlenen dünyanın belli başlı bütün kitap fuarlarına gönderseler, böylelikle her çıkan yeni kitabı görsem, dünyanın büyük kentlerinin bütün eski kitapçılarını, yüzyıllık sahaflarını gezsem, sevdiğim yazarların ilk baskılarını toplasam, en eski, en değerli el yazmalarını incelemem için dikkatime sunsalar, kitap yapımında kullanılan bütün kâğıt çeşitlerini görsem, dokunsam, kitap kapakları, tasarımları yapan grafikerlerin uluslararası oturumlarına gözlemci olarak katılsam, dünyanın belli başlı en büyük kitabevlerinden, en kenarda kıyıda kalmış, küçük ama özel yayınevlerine kadar bütün önemli kuruluşlar beni yeni dönem programları konusunda bilgilendirseler, en uzak, en küçük ülkelerin yayıncılık hayatından da, yeni yazarlarından da anında haberdar olabileceğim bir iletişim ağı kurulsa, kitapların birçoğunu kendi yazıldıkları dilde okuyacak kadar çok dil bilsem, joyce'u ingilizcesinden, genet'yi fransızcasından, dostoyevski'yi rusçasından, marquez'i ispanyolcasından, brecht'i almancasından, eco'yu italyancasından, pessoa'yı portekizcesinden, mişima'yı japoncasından okuyabilsem, fena mı olur? Sofokles, İbsen, Horatius, Hayyam, Farabi, Shakespeare, Tagore, Knut Hamsun, Mahabbarata, Avesta, Nibelungen, Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, Tarjei Vesaas, İbni Haldun, Molière, Danilo Kiş, Borges, Konfüçyüs, Çiçero, Tolstoy, bütün bunları kendi dillerinde, dönemlerinin dillerinde okuyabilsem, Commedia dell'arte oyunları, binbir gece masallarının arapçası, incilin aramicesi, ipek kâğıtlara yazılan on birinci yüzyıl haikuları, süryanca dualar, sümer yazıtları, çivi yazısı, mühürlerde ve paralarda gömülü bütün sözcükler, lahitlerde ve alınlıklardaki saklı sözler, afrika maskelerinin gizli ve kutsal işaretleri, simli el yazmaları, ceylan derisine yazılmış kitaplar, pehlevice masallar, mayaların gün işaretleri, azteklerin simgeleri, hepsi hepsi gözlerimin önünde sırlarını bir bir açsalar, hitit kraliçesi puduhepa'nın rüyalarını yazdırdığı kil tabletleri okuyabilsem, medce türkü söyleyebilsem, kelt dilinde şiirler, aşk ve rüzgâr sözcükleri bilsem, uygurca rüya görsem, latince ilahiler okusam, platon'un mağarasında gölgelere karışsam, arjantin tangolarının argosunu bilsem, çingenelerin yüzyılların yollarına bıraktıkları sözcükleri derlesem, aristo'nun komedya'sını bulsam, bütün büyücülerin unuttuğu sihirli kelimeleri ben hatırlasam, onca yıl dünyanın onca yerinden toplayıp biriktirdiğim bütün el yazmalarından, en yeni kalın ciltli güzel kitaplara varana dek hepsini raflarına dizdiğim bir ilkçağ tapınağına benzeyen kitaplığımın serin, küçük, yeşil avlusunda sonsuz uykuma yatsam, ardımdan insanlar, ne güzel mesleği vardı deseler, yazık, okuyacak ne çok kitabı kaldı geride. 6 Ekim 1993 Latife Tekin Gözlerimde, bütün yüzeyleri genişletip büyüten bir ışıkla dolaştığım günler... ruhumla aynı âlem içinde kaldı. Yıllardır, gözlerimin benden ayrı, başka bir macerası var. Okurken, neyi seyrettiğimi bilmiyorum. Bilsem, kulağıma "anlam ne tuhaf şey" diye fısıldanmazdı. Bilge Karasu Okur kitap arar, ama kitabın da okuru bulduğunu ben çok gördüm. Açıklanabilir bir şey söylemiyorum belki, ama "rastlantılar"ın çoğu, açıklayamadığımız için rastlantı görünmez mi? 18. yüzyılın ortalarından bu yana "Serendipli Üç Şehzade" masalından yola çıkılarak türetilmiş bir sözcüğü var İngilizcenin: Serendipity; aranmakta olmayan değerli/hoşlanılır bir şeyin insanın karşısına çıkıvermesi anlamında kullanılan... Elbette, aranmayan şeyin bulunması, olacak şey değil. ne var ki, "aranmama"yı "o anda aramakta olmamak" ya da "aranması gerektiği düşünülen yerde aramakta olmamak" diye yorumlarsak, birçok kişinin bu "Serendiplilik"ten (az ya da çok) pay aldığını kestirebiliriz. Serendip yağmuru benim de tarlama yağmıştır ara ara. Bir şey (birçok şey, bir şeyler) öğrenmek için okumak, kitaba yönelmek ile, haz duyulduğu (duyulacağı umulduğu) için okumağa oturmak arasında, gerçekten, büyük bir fark var mı? Hatta, herhangi bir fark var mı? Bir buçuk yıl önce (18 yıl oturduğum evden) taşınmam gerektiğinde kitaplarıma duyduğum öfkeyi yakınımdakiler hep gördü. "Hepsini satacağım!" diye haykırdım, söylendim günlerce. Bir iki "göstermelik" satış bile oldu. En az iki bin kitabımı satmağı tasarladım ya, bugüne dek bu satışın bir parçacığı bile gerçekleştirilmiş değil. Yıllardır "satacağım" deyişim, beceremeyişim, "mal"ımdan kopamayışım, alıcı çıksın diye beklerken alıcı çıktığında mızmızlanacağımı bilişim... Çok başka bir düeyde de tanıdığım bir duygu bu... Çok sevdiğiniz, birlikte yaşadığınız, onsuz bir yaşamı düşünemeyeceğiniz ölçüde yaşamınızda yer etmiş kişiler, varlıklar da, sizi bezdirir arada bir; içinizin bir kuytularında onlardan kurtulmak istersiniz. O kişinin, o varlığın ölümünü bile geçirirsiniz usunuzdan, getirirsiniz gözünüzün önüne (tepkinin ilkelliği apaçık değil mi?). Kendinizi ne kadar bağlı (sözcüğün hemen hemen her anlamıyla bağlı) duyduğunuzun bir kanıtı değil midir zaten bu çılgınlık? Çılgınca şeyler düşündüğünüzü de bilirsiniz (suçluluk duygularından falan söz etmiyorum) çünkü bilirsiniz ki onsuzluk, sizin de, en azından bir parça ölümünüzdür. Düpedüz. Evet, ölenlerin ardından yaşandığını, ölenle ölünmediğini herkes bir gün öğrenir. Ama eksilerek, azalarak, sakatlanarak, bir yeri koparak yaşandığını... Oysa nesne-kitaptan kopabilmek gerek. Metinden ya da öğreniden söz edilecek olursa diyeceğim ki, o metin sizi uzun ya da kısa süre besleyip yaşattıysa, ondan da kopmasını öğrenmek gerek. Özümlediğinizle yetinebilirsiniz. Vazgeçilmez metinler yok mu? Elbette var; ama ne kadar az! –Ne Kitapsız, Ne Kedisiz’den, 1987 Juan Goytisolo Yazın metni, ne hemen tanınmayı, ne de okur yığınını anında büyülemeyi amaçlar. Kendisini "okuyacak" kişileri aramaz, "yeniden okuyacak" kişileri arar, yoksalar, çoğu zaman onları yaratmak zorunluğunu duyar. İz bırakmak, dal budak salmış yazın ağacına bir şeyler eklemek emelinde olan yazar önceden bilinen bir ortamda, her zamanki alıcının alışkın olduğu kurallara uyarak salınmak yerine, okurun düzenini sarsmaktan, onu bilmediği bir alana sürüklemekten ve ona işin daha başından, kurallarını hiç bilmediği bir oyun önermekten çekinmez. Okurun başlangıçtaki o şaşkınlığı, işaret levhalarının bulunmadığı, ayak basılmamış bir alanda o el yordamıyla ilerleyiş, kitabın sunduğu yeni ülkeyi düzenleyen gizli yasaları keşfetmek için gerilere dönme gereği, ona okumanın keyfini tattıracak, yenilikçi sanat önerisini özümsemek için onu yazarla işbirliği yapmaya yöneltecektir. Farkına bile varmadan, okur "yeniden-okur"a dönüşecek, o sayede okuduğu ve sonra yeni baştan okuduğu metni kuşatma ve ele geçirme harekâtına etkinlikle katılacaktır. Yine aynı noktayı vurguluyorum, yazınsal yapıtın yazarı, sonuçta, yalnız yapıtını değil, kendi ölçüsüne uygun okur yığınını da yaratır. Zamandışı metin yaratıcılarından oluşan yıldız kümesini, eleştirmenlerin şakşakladığı, okur oylamasından geçmiş yazarlar topluluğundan ayıran şey, bunların gözüne hâlâ yaşıyormuş gibi görünen yapıtları berikilerin sönmüş ya da ömrünü tamamlamış saymalarıdır. Çağdaşlarının alkışlarına ya da sitemlerine duyarsız olan yaratıcı yazar, çevresinin ölü uğraştaşlarla sarılı olduğunu bilir; hem de istedikleri kadar çırpınsınlar, onur belgeleri ve ödüller biriktirsinler, iskeletsiz birtakım akademisyenler misali, ölümsüzlüğün şanına ermeyi düşlesinler... Benim dünyam, örneğin, çağın modalarına ve yasalarına yabancı bir yazınsal kuraldışılıklar ve istisnalar burcuna dağılmış bulunmaktadır; dipdiri, sapsağlam varlıklarını sürdüren yazarların yüzlerce yılın ötesinden adımlarıma ışık tuttuğu mezarlıklardadır; izleri acımasızca silinip gidecek olan, varlıktan yoksun gölgelerin büyük keşmekeşinin sahnesinde değil. O yazarların, yazılı sözün aracılığıyla, yaşayanlarla böyle kaynaşmaları ne sınır tanır, ne çağ. Yapıtlarını saydığım yazarlarla, değişik kültürlerden ve alanlardan gelme başka yazarlara, İbni Arabî ile İbni El Fârid'e, Rabelais ile Swift'e, Flaubert ile Biely'ye, Svevo ile Céline'e, Arno Schmidt ile Lezama'ya o yoldan bağlıyım. Onların göz kamaştırıcı parıltısı, şamatacı ve sıradan çağdaş yazınımızın bir görünüp kaybolan hayaletleriyle dolu bu evrende nereye gitsem benimle birlikte geliyor. Ancak onların sert kabuğunu delip, "çekirdeğin çekirdeği"ne ulaşan, kabilenin değer ölçütlerine sırt çevirip onların gerçeğini ele geçiren kişi bu eşsiz, yinelenmesi olanaksız sese erişecektir: garipliğiyle öbürleri arasından seçilen ve alışılmış taklitçiler alayının öykünme ya da benzetmelerine cesaret vermeyen sese. Yazın tarihi, her yazının tarihi, yüzyıllar boyunca kendi aralarında söyleşiyora benzeyen ve eşsizliklerinin tılsımıyla bizi büyüleyen o benzersiz seslerin tarihidir. –Yeryüzünde Bir Sürgün’den |

|

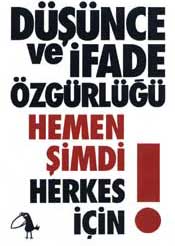

1995

Düşünce ve İfade Özgürlüğü Hemen Şimdi Herkes İçin Bütün okurlarımızın Türkiye’de kitap yayıncılığının asude bir meslek, salt bir kültürel ve ticari faaliyet olmadığını gayet iyi bildiklerini tahmin ediyoruz. Metis Yayınları’nın bütün geçmişi boyunca Düşünce ve İfade Özgürlüğü için mücadele etmek gündemimizin birinci maddesi oldu, olmak zorundaydı. Biz yayıncılar, kendi asli faaliyetimizi sürdürmenin yanı sıra her zaman üstünde yürüyeceğimiz yolu da döşemek zorundaydık. Bugün de hâlâ öyledir, çünkü anayasal bir hak olan Düşünce ve İfade Özgürlüğü, en başta devletin, ama aynı zamanda sivil dünyanın/toplumun içinden de çeşitli faillerin kimi zaman siyasal, kültürel, kimi zaman doğrudan şiddete dayalı engellemeleri, baskıları, bahaneleri ve bozundurmaları ile karşı karşıyadır. Türkiyeli halihazırda bu anayasal hakkını kullanamamaktadır. İşte 1995 yılı bu mücadelenin tırmandığı anlardan biriydi. 22 yayınevi ortaklaşa yaptığımız kampanyayla toplumu, tabii ki en başta okurlarımızı, bu haklarına sahip çıkmaya çağırdık. Bilindiği gibi, Türkiye’de devletin ve muhafazakar çevrelerin temel argümanı, Türkiye toplumunun bu tür hakları doğru bir biçimde kullanmak için henüz yeterli seviyede olmadığıdır. Biz ise tam tersini düşünüyoruz: Toplumun çocuksu, olgunlaşmamış kalması, demokratik eğilimlerin güdüklüğü, tam da bu hakkın toplum tarafından özgürce kullanılamamasından kaynaklanıyor. Bireylerin ya da toplumun bu hakkı kullanmak için reşit olacağı ileri bir tarihin beklenemeyeceğini, sorunun "hemen şimdi", hiçbir bahaneyle ertelenemeyecek kadar acil çözüm beklediğini ileri sürüyoruz. "Herkes İçin" derken de kastımız şuydu: Düşünce ve İfade Özgürlüğü genellikle yazar çizerlerle, entelektüellerle, aydınlarla birleştirilir. Oysa bu hak herkes için gereklidir. Özellikle de halk için gereklidir. Düşünce ve İfade Özgürlüğü, entelektüellerin, aydınların bir fantazisi değildir, bir demokrasinin çalışması için gerek şarttır. 1995’te bu düşüncelerle yazdığımız ortak açıklama ise şöyleydi: Ülkemizde bugün düşünen, yazan, hatta yayınlayan hapiste. Son olarak da Özgür Ülke gazetesi bombalandı. Bu, toplumumuzda düşünce özgürlüğüne olan tahammülsüzlüğün boyutlarını göstermiştir. 20. yüzyılda, konuşan, yazan aydınlarının sürülmesine, hapse atılmasına, hatta öldürülmesine seyirci kalan yegâne "demokratik hukuk devleti" Türkiye'dir. Düşüncenin engellenmesi, toplumsal barışın önündeki bütün yolları tıkamaktadır. Bizler, Düşünce ve İfade Özgürlüğünü engelleyen, her türlü yasa ve uygulamanın derhal kaldırılmasını istiyoruz. Toplumumuzu, bizimle birlikte bu hak ve özgürlüklere sahip çıkmaya çağırıyoruz. Afa, Alan, Ayrıntı, BDS, Belge, Boyut, Can, Cep, E- Anahtar, Hil, İletişim, İmge, Kavram, Kıyı, Metis, Öteki, Pan, Papirüs, Sarmal, Say, Ümit ve Varlık Yayınevleri |

|

1995

Belleksiz Toplum Yoktur Kitaplar hem bireysel hem toplumsal hafızanın temel unsurlarıdır. 1995 yılında, yayınlanmış Metis kitaplarından, farklı yazarlardan birer cümlelik alıntılar yaparak aşağıdaki kolaj metni oluşturuyor editörlerden Müge Gürsoy Sökmen. Biz bir yayınevinde biraraya gelen seslerin, az çok tutarlı bir bütün oluşturduğuna, oluşturabileceğine inanıyoruz. Yayınevine kişiliğini veren de budur. Metis koleksiyonunu oluşturan yazarların ve kitapların toplamı rasgele değildir. Bu kısa metni, birbirlerinden çok farklı seslerin nasıl birbirine eklemlenebildiğine örnek olarak okuyabilirsiniz: Belleksiz Toplum Yoktur. Çocuklarını kurban etmeyi göze alan; yoksulluk, çaresizlik, cehalet gibi erdemlere sarılarak katliamların üstünden "aman, bir tatsızlık çıkmasın" duygusuyla atlayıveren toplumlar vardır. – YILDIRIM TÜRKER. Sonuçta iki seçim kalır ve başka hiçbir şey / İntihar ve Kötülükten başka. – MURATHAN MUNGAN. Fikirlerimizin büyük çoğunluğu, hiç de akıl ürünü değildir, göreneklerden ibarettir; mekanik ve anlaşılmazdırlar ve bize baskı yoluyla benimsetilmişlerdir. – ORTEGA Y GASSET. Bendim ona, hiçbir düşünce seni ağına düşürmemeli, diyen; yolunu tek başına bul, diyen; şimdi de dayanıksızlığının tutsağı değil mi? – BİLGE KARASU. Edebiyatta, felsefede, bilimde, düşünme ve anlatım biçimiyle ilgili, sorgulamadan kabul ettiğimiz pek çok niteliğin, insanoğlunun kendi doğasından değil, yazı teknolojisinin bilincimize sunduğu olanaklardan kaynaklandığını anlayınca, insan kimliği kavramımızı yeni baştan irdelemek zorunda kalmış bulunmaktayız. – WALTER J. ONG. Tavşan besleyen, midesi ile özgürlüğü arasında bir türlü karar veremeyen bir canlıyla uğraşmayı da öğrenmelidir. – ORUÇ ARUOBA. Yaşam, sıradanlığını sürdürdükçe, diyeceğim insanlar işine gücüne baktıkça, köklü bir biçimde zorlanmadıkça oldukça açıktır. Sıradanlık bozulunca açıklık çözülür, tuhaf düşünceler, algılar, duygular baş gösterir. Düşünceler, tıpkı kelebekler gibi, yalnızca varolmakla kalmaz; gelişir, başka düşüncelerle ilişkiye girer, etkide bulunurlar. – PAUL FEYERABEND. Ancak ölü kelebekler uçuşur yelle birlikte. – ERTUĞRUL OĞUZ FIRAT. Ne de olsa, yaşamımız boyunca hepimizin karşısında bir gözdağı olarak duran bir yazgı "aklını yitirme" kavramı. Bir zamanlar saçma, olanaksız, benim değil, başkasının başına gelebilecek bir şey olarak niteleyeceğim bir olasılıktı bu. – KATE MILLETT. Sabır, ümitten daha uzun ömürlü olabilir. – URSULA K. LE GUIN. Dolayısıyla bizler, ne her türlü çoğulluğun, çeşitliliğin reddedildiği homojen bir zemine mahkûmuz, ne de içinde hiçbir homojenliğin, hiçbir ortak tartışma alanının olmadığı bir çoğulluk zeminine. Tersine, çoğulluk ve birlik karşılıklı olarak birbirlerini güçlendirirler ve birbirlerine ihtiyaçları vardır. – OLIVIER ABEL. Dolayısıyla, uç veren buğdaya kulak kabartmak, gizli kalmış potansiyelleri yüreklendirmek, tarihin saklı tuttuğu tüm bir arada yaşama eğilimlerini dürtüklemek; ayrıca bütün bu yeni toplumsal ifade biçimlerini şaşırmaksızın, tiksinmeksizin, karşı çıkmaksızın karşılamaya hazır olmak gerekmektedir. – C. LÉVI-STRAUSS. Heterojenliği ve farklılığı tanıyabilen, ama her birimizi yalnızca bir yönle tanımlayan bir özcülüğe teslim olmayan, yeni bir politik dil bulmak zorundayız. – ANNE PHILLIPS. |

|

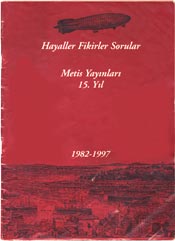

1997 I 15. Yıl

Hayaller Fikirler Sorular 1997 sonbaharında Metis’in 15. yaşını kutluyoruz. Geride bıraktığımız döneme baktığımızda çabalarımız üç tema etrafında yoğunlaşıyor: Hayaller Fikirler Sorular. Belli ki bunlar Türkiye’deki genel akıntının tam tersi yönde. Hayal kurmayı, olağan gidişatın sınırlarını zorlamayı, yaratıcı davranmayı önemsiyoruz ve okurlarımıza bunu yansıtmaya çalışıyoruz. Fikirlere, fikirlerin önemine, zihinsel alışverişe, eleştirel düşünmeye ve bunların birikerek bir alışkanlık halini almasına vurgu yapıyoruz. Hiçbir verili düşünce ve söylemin eleştiriden azade olmadığını, her yerleşik düşüncenin irdelenmeye, sorgulanmaya muhtaç olduğunu vurgulayarak, tekrar tekrar soru sormak istiyoruz. 1929 yılında İstanbul semalarında bir zeplin. Simgesel bir önemi var bu zeplinin. Hem insan yaratıcılığını ve özgürlüğünü simgeliyor, hem Türkiye ile ilgili bir kara deliği hatırlatıyor: Fikirler, tasarılar, mallar ve teknik Batı’dan geliyor bu ülkeye. Bu olgu Türkiye’de birçok insanın çabasını beyhudeleştiriyor, "cami önünde salyangoz satıcısı" konumunu doğuruyor. Ülkenin siyasi, kültürel ve bürokratik seçkinleri bu durumu korumayı ve sürdürmeyi tercih ediyorlar, bunun için ellerinden geleni yapıyorlar. Bir yerde seçkinliklerinin koşulu bu. Geniş kitleler sanattan ve nitelikli bir eğitimden bile isteye uzak tutuluyor. Öyleyse akıntıya karşı kürek mi çekiyoruz? Tam olarak değil. Çünkü ortaya atılan yeni fikirler gitgide ana akıntıların tersi yönde alt akıntılar oluşturuyor. Türkiye değişiyor. Daha önce ağza alınamayanlar tartışılabiliyor, bir süre sonra yeni kuşaklar bu fikirlerin içine doğuyor. |

|

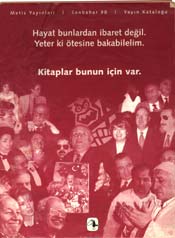

1998

Hayat bunlardan ibaret değil. Yeter ki ötesine bakabilelim Kitaplar bunun için var 1998 tipik bir Türkiye yılı. Ama galiba olup bitenler bütün bir toplumda genelleşmiş bir bezginlik yarattı. Adı konmuyorsa da bir tür iç savaş sürüyor. Trafik canavarı, yükselen Siyasal İslam, Kürt sorunu ve bunlar bahane edilip "derin devlet" lafzının arkasına gizlenerek yürütülen devlet terörü, Demireller, Çillerler, Erbakanlar, soyguncu işadamı ve işkadınları, hırsız siyasetçiler ve Fethullah hocalar gündelik hayatı zaptediyorlar. Bu koşullarda hayatta kitaba yer yok. Kitaplar ve onların temsil ettiği her şey daha baştan kaybetmiş gibi. Politik alanın sonu gelmiş gibi. Bir savaşın aciliyetinde ve aktüelliğinde düşünceye yer yok. 1998’den itibaren bu ruh hali yıllarca varlığını sürdürecek, 99 İzmit depremiyle, siyasi cinayetlerle, toplumun gitgide militaristleşmesiyle katmerlenecek. Hayatın bunlardan ibaret olmadığını hatırlatmak istiyoruz. Direnme gücünün ancak bu dayatılanların ötesine bakabilmekten, manzaranın arkasını okuyabilmekten kaynaklanacağını söylüyoruz. Kitapların tam da bu nedenle var olduğunu söyleyerek, kitaplara hayatımızda yer açmak istiyoruz. |

|

2002 I 20. Yıl

Böylece 20 yıl geçti. Bu süre içinde emekleri, fikirleri, destekleriyle sayısız insanın katkısı oldu yayınevine. Tümüne, kitabevi ve dağıtım çalışanlarına ve devam edebilmemizde asıl gücü veren okurlarımıza teşekkür ediyoruz. EMEKLERİ, FİKİRLERİ, DESTEKLERİYLE METİS YAYINLARI’NI VAREDEN, Abdullah Onay, Abdullah Şen, Abidin Dino, Adalet Ağaoğlu, Adnan Ekşigil, Adnan Yalçınlar, Afşar Timuçin, Agah Özgüç, Ahmet Cemal, Ahmet Çiğdem, Ahmet Doğukan, Ahmet Güntan, Ahmet Hakan, Ahmet İnsel, Ahmet Kehri, Ahmet Kocaman, Ahmet Necdet, Ahmet Oktay, Ahmet Sipahioğlu, Ahmet Soysal, Aksu Bora, Alaettin Aksoy, Alev Alemdar, Alev Türker, Ali Akay, Ali Babaoğlu, Ali Bucak, Ali Çakıroğlu, Ali Ekeyılmaz, Ali Erdemci, Ali Menteş, Ali Tükel, Alper Oysal, Arda Denkel, Aron Aji, Aslı Biçen, Aslı Karasuil, Asuman Erdost, Aşkın Demir, Atilla Akar, Atilla Birkiye, Arzu Etensel İldem, Arzu Gökçen, Avi Pardo, Aybars Erözden, Aydın İşisağ, Aydın Uğur, Aykut Çelebi, Aykut Derman, Aynur İlyasoğlu, Ayperi Ecer, Aysel Bora, Ayşe Buğra, Ayşe Durakbaşa, Ayşe Eyüboğlu, Ayşe Gül Altınay, Ayşe Kadıoğlu, Ayşe Öncü, Ayşe Özmen, Ayşe Tütüncü, Ayşegül Denkel, Ayşegül Devecioğlu, Ayşen Gür, Ayşenur Aslan, Balkan Naci İslimyeli, Banu Büyükkal, Banu Gürsaler, Barbaros Altuğ, Barış Müstecaplıoğlu, Barış Pirhasan, Başak Ertür, Behiç Ak, Bejan Matur, Belma Aksun, Beril Eyüboğlu, Berke Vardar, Berna Ülner, Bilge Karasu, Bilgin Saydam, Bülent Akkoç, Bülent Erkmen, Bülent Somay, Bülent Tanatar, Bünyat Dinç, Cahide Birgül, Can Kurultay, Canan Arın, Canan Çakaloz, Candan Etili, Celal Kanat, Celal Üster, Celil Oker, Cem Atbaşoğlu, Cem Erciyes, Cem Soydemir, Cem Taylan, Cemal Bali Akal, Cemal Ener, Cemal Güzel, Cengiz Can, Cengiz Kuşçuoğlu, Cevat Çapan, Cüneyt Akalın, Cüneyt İşcan, Cüneyt Türel, Cüneyt Vardar, Çağla Bakış, Çağlar Keyder, Çağlar Tanyeri, Çiğdem Erkal İpek, Deniz Akidil, Deniz Bilgin, Deniz Erksan, Deniz Göktürk, Deniz Kandiyoti, Deniz Sezer, Devrim Sevimay, Didem Baskın, Dilek Barlas, Dilek Çokluk, Doğan Hızlan, Doğan Özlem, Dost Körpe, Duygu Köksal, Ece Temelkuran, Egemen Berköz, Elif Daldeniz, Elif Naci, Elif Şafak, Emel Abora, Emel Ergun, Emil Galip Sandalcı, Emil Keyder, Emine Özkaya, Emre Senan, Ender Gürol, Engin Geçtan, Enis Sakızlı, Erdağ Aksel, Erdal Akalın, Erdim Öztokat, Erendiz Atasü, Ergin İnan, Erol Akyavaş, Erol Hızarcı, Erol Köktürk, Erol Öz, Ertuğrul Kürkçü, Ertuğrul Oğuz Fırat, Esin Talu Çelikkan, Evren Erem, Ezel Akay, Falih Köksal, Faruk Şüyun, Fatih Erdoğan, Fatih Özgüven, Fatma Akerson, Fatma Taşkent, Fatma Tülin Öztürk, Fatmagül Berktay, Fehmi Çalmuk, Fehmi Hasanoğlu, Ferda Erdinç, Ferda Keskin, Ferhan Ertürk, Ferhat Ünlü, Ferhunde Özbay, Feride Çiçekoğlu, Feridun Andaç, Ferruh Gencer, Ferruh Yılmaz, Fethiye Çetin, Fevzi Karakoç, Fevziye Sayılan, Feza Kürkçüoğlu, Fikret İlkiz, Filiz Aygündüz, Filiz Bingölçe, Firuz Kutal, Fuat Toper, Füsun Akatlı, Füsun Üstel, Gamze Varım, Giovanni Scognamillo, Gökhan Çetinsaya, Gönül Çapan, Gül Işık, Gülay Köksu, Gülay Kutal, Güler Güven, Gülnur Savran, Gülseli İnal, Gülsün Karamustafa, Gülşat Aygen, Gündüz Vassaf, Güniz Can, Gürol Irzık, Güven Savaş Kızıltan, Güven Turan, Güzide Güney, Güzide Gürbüz, Güzin Dino, Güzin Özkan, Hakan Altınsay, Hakan Denker, Hakan Yücel, Haldun Bayrı, Haldun Gülalp, Halil Gökhan, Halil İbrahim Özcan, Haluk Barışcan, Hamdi Ateş, Haluk İnanıcı, Hamit Sümbül, Haşim Sümbül, Haşmet Topaloğlu, Hayrettin Aydın, Hıdır Göktaş, Hilmi Bitim, Hilmi Yavuz, Hulki Aktunç, Hülya Ekşigil, Hür Yumer, Hüseyin Karabey, Hüseyin Sorgun, Hüseyin Sönmez, Hüsnü Arkan, Immanuel Wallerstein, Işık Abel, Işık Ergüden, Işık Gencer, Işın Bengi, Işın Gürbüz, İbrahim Altınsay, İbrahim Somay, İhsan Bilgin, İhsan Yılmaz, İlhan Tekeli, İoanna Kuçuradi, İpek Babacan, İpek Çalışlar, İrfan Sayar, İrma Dolanoğlu Çimen, İskender Savaşır, İsmail Kara, İsmail Yerguz, İsmet Doğan, İsmet Zeki Eyüboğlu, Jale Parla, Jean Stein, Joelle Danon, John Berger, Kadri Gürsel, Kaya Şahin, Kemal Atakay, Kemal Başar, Kemal Sayar, Kerem Çalışkan, Kezban Akçalı, Kezban Arca Batıbeki, Komet, Kutluğ Ataman, Lâle Müldür, Laleper Aytek, Latif Demirci, Latife Tekin, Levent Akın, Levent Aydeniz, Levent Cinemre, Levent Efe, Levent Kavas, Levent Mollamustafaoğlu, Levent Yılmaz, Leyla Erbil, Leyla Gülçür, Leyla Navaro, Lokman Şahin, Mahmut Mutman, Mahmut Temizyürek, Manuel Çıtak, Maria Sarı, Mehmet Ali Gencer, Mehmet Budak, Mehmet Ergüven, Mehmet Güleryüz, Mehmet Güreli, Mehmet İnhan, Mehmet Moralı, Mehmet Sönmez, Mehmet Tanju Kaya, Mehmet Tekin, Mehmet Ulusel, Mehmet Yaşın, Melahat Togar, Melih Baş, Melih Gürsoy, Meltem Ahıska, Meltem Cansever, Memet Fuat, Meral Özbek, Merve Erol, Mete Çubukçu, Metin And, Metin Çetin, Metin Kaçan, Meyda Yeğenoğlu, Mısra İlden, Murat Belge, Murat Hocaoğlu, Murat Kelkitlioğlu, Murat Koçak, Murat Uyurkulak, Murathan Mungan, Mustafa Arslantunalı, Mustafa Ata, Mustafa Atakay, Mustafa Horasan, Mustafa Yılmazer, Mustafa Ziyalan, Müfide Pekin, Müfit Özdeş, Müge İplikçi, Müge Sözen, Müjgân Halis, Mürşit Balabanlılar, Nadire Mater, Nail Satlıgan, Naim Dilmener, Nasuh Barın, Nazan Aksoy, Nazlı Korkut, Nazlı Öktem, Nazmiye Güçlü, Necati Erkurt, Necdet Neydim, Necdet Teymur, Necmettin Sevil, Necmi Zeka, Necmiye Alpay, Nedim Şener, Nedret Öztokat, Nedret Pınar, Nermin Menemencioğlu, Nesrin Kasap, Nesrin Tura, Neşe Benli, Nezihe Meriç, Nigar Çapan, Nihal Akbulut, Nilüfer Göle, Nilüfer Güngörmüş, Nilüfer Kuyaş, Nimet Tuna, Niyazi Zorlu, Nuran Kutlu, Nuran Yavuz, Nuray Mert, Nurdan Gürbilek, Nurettin Elhüseyni, Nurhan Borand, Nuri Akbayar, Nursel Duruel, Nükhet Gökaltay, Oğuz Cebeci, Oktay Döşemeci, Oktay Özel, Olivier Abel, Onat Kutlar, Onur B. Kula, Oral Çalışlar, Orhan Duru, Orhan Koçak, Orhan Pamuk, Orhan Suda, Oruç Aruoba, Osman Çakaloz, Osman Senemoğlu, Ömer Aslan, Ömer Demircan, Ömer Laçiner, Ömer Madra, Özkan Gözel, Peral Bayaz, Petek Kurtböke, Pınar Besen, Pınar İlkkaracan, Pınar Kazma Çınar, Pınar Kür, Ramazan Yavuz, Raşit Çavaş, Reha Çamuroğlu, Reha Erdem, Remzi Ayhan, Rıza Tura, Roni Margulies, Roza Hakmen, Ruşen Çakır, Sabiha Banu Yalkut, Sabir Yücesoy, Sabri Gürses, Sadık Karamustafa, Sadık Yemni, Saffet Günersel, Saffet Murat Tura, Salih Ecer, Saliha Paker, Sami Oğuz, Sedef Öztürk, Sefa Kaplan, Selahattin Erkanlı, Selahattin Özpalabıyıklar, Selçuk Demirel, Selda Arkan, Selim İleri, Selim Yazgan, Sema Postacıoğlu, Semih Vaner, Semra Somersan, Sennur Sezer, Serdar Çömez, Serhan Ada, Serhan Keser, Serhan Yedig, Serkan Seymen, Sermet Tolan, Serpil Çakır, Serra Yılmaz, Sevgi Sanlı, Sevgi Tamgüç, Sevinç Yavuz, Sevkuthan Karakaş, Sezer Duru, Sırma Köksal, Sıtkı M. Erinç, Sibel Gökçen, Sinan Fişek, Siren İdemen, Soli Özel, Sosi Dolanoğlu, Sönmez Güven, Stella Ovadia, Suat Karantay, Suavi Güney, Sumru Ağıryürüyen, Suna Aras, Sunay Girgin, Sungur Savran, Süha Derbent, Süleyman Seyfi Öğün, Süleyman Özkur, Şadan Karadeniz, Şahika Yüksel, Şahin Beygu, Şara Sayın, Şavkar Altınel, Şebnem Kara, Şebnem Susam, Şemsa Gezgin, Şemsa Özar, Şen Süer, Şengül Kılıç, Şerafettin Turan, Şerif Mardin, Şeyhmus Diken, Şiar Yalçın, Şirin Tekeli, Taha Parla, Tahsin Yücel, Talat Parman, Talat Sait Halman, Talat Tekin, Tan Oral, Tanıl Bora, Tansu Açık, Tarık Dursun K., Tarık Erdoğan, Tayfun Atay, Tayfun Demir, Teoman Aktürel, Tevfik Turan, Timuçin Gürer, Timuçin Unan, Tomris Uyar, Tonguç, Tuba Çele, Tuğrul Eryılmaz, Tuğrul Paşaoğlu, Tuna Erdem, Tuncay Birkan, Turan Dursun, Turgay Kantürk, Turgay Kurultay, Turgay Tekatan, Turhan Günay, Türker Armaner, Uğur Kökden, Ulus Baker, Ülker Gökberk, Ülkü Tamer, Ümit Kıvanç, Ünal Nalbantoğlu, Vaner Alper, Vedat Günyol, Vehbi Hacıkadiroğlu, Veysel Atayman, Victoria Holbrook, Vivet Kanetti, Yael Navaro Yaşın, Yahya Koçoğlu, Yaprak Zihnioğlu, Yaşar Avunç, Yaşar Çabuklu, Yaşar Kemal, Yavuz Erten, Yeşim Erim, Yeşim Tükel, Yetkin Başarır, Yıldırım Koç, Yıldırım Türker, Yıldız Olgun, Yılmaz Öner, Yiğit Bener, Yurdanur Salman, Yusuf Eradam, Yusuf Karıksız, Yücel Göktürk, Zafer Aracagök, Zafer Toprak, Zehra Toska, Zehra Yılmazer, Zeynep Arman, Zeynep Avcı, Zeynep Direk, Zeynep Oral, Zeynep Sayın, Zühtü Bayar, Zülfikâr Ali Aydın ve adını sayamadığımız daha birçoklarına, KİTABEVİ VE DAĞITIM ÇALIŞANLARINA, DEVAM EDEBİLMEMİZ İÇİN GÜÇ VEREN OKURLARIMIZA TEŞEKKÜR EDİYORUZ. |

Kişisel Veri Politikası

Aydınlatma Metni

Üye Aydınlatma Metni

Çerez Politikası

Metis Yayıncılık Ltd. İpek Sokak No.5, 34433 Beyoğlu, İstanbul. Tel:212 2454696 Fax:212 2454519 e-posta:bilgi@metiskitap.com

© metiskitap.com 2026. Her hakkı saklıdır.

Site Üretimi ModusNova

| İnternet sitemizi kullanırken deneyiminizi iyileştirmek için çerezlerden faydalanmaktayız. Detaylar için çerez politikamızı inceleyebilirsiniz. | X |